We are a tactile species, the

weight and shape and texture of objects eliciting endless thoughts, conjectures

and connections in our minds. The solidity of a pebble in our hand contains all manner of

possibilities; we can rub it gently and reflect on the world around us, or send

it skimming over the waves. It is something we can add to a sand castle, or

turn into a cannon ball to use against its sandy towers.

In another age those who

examined stones would consider how to crack it open to make sharp edged tools: one

blade would be set aside for gutting fish or cutting meat from the bone, while

another blade would be designated as a surgical tool to slice away gangrenous

flesh or to cut an umbilical cord. But before any blade is made, or game is

played or any moment of reflection begun, there is that moment of touch. It is

touch, not ‘the word’, that is the beginning of our story as a species.

Even the spoken word is a

tactile phenomenon, relying on the pressure of tongue against teeth and palate,

of lip upon lip. Touch plays a role too in how we receive the spoken word. Is

the air touching our skin cold and damp or is it cool and refreshing; is the

seat beneath our backside hard or soft; are we sitting or standing in a roomy

space or are we part of packed in crowd? All these things will impact on how we

engage with words spoken to us.

How we record and take

cognisance of those spoken words is also effected by touch. In this ever

connected online Information Age an increasing amount of writers, including myself, claim

that the physical act of writing, of putting pen or pencil to paper, is the key

to successful research and writing. The movement of fingers and hand, the

kinetic choreography and calligraphy of bone, skin and cartilage working

together to scratch a mark on blank paper is an incredibly magical and

liberating act. It not only leaves an impression on paper but in the heart and

the head of the writer.

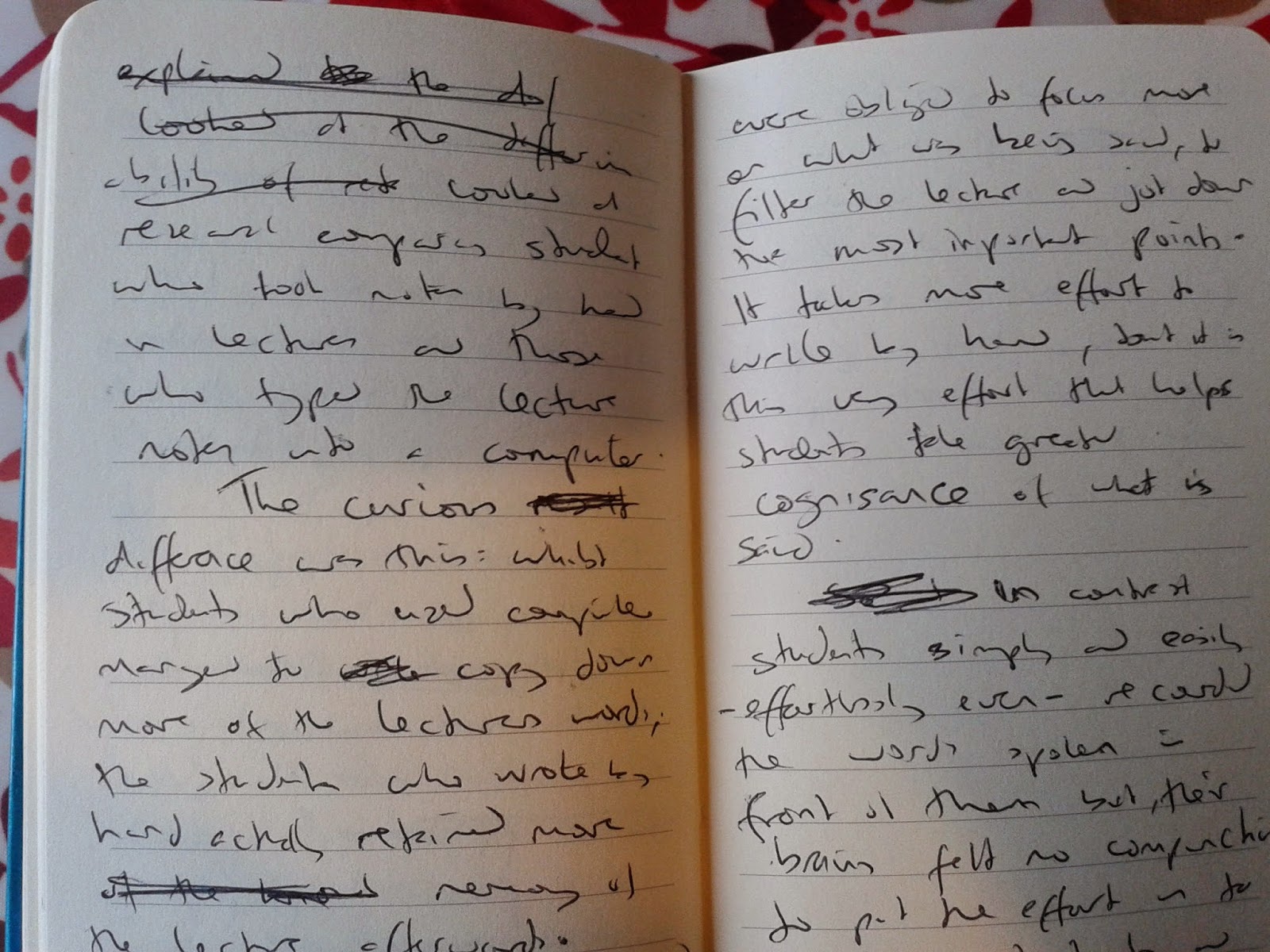

Science

is beginning to catch up with the gut instinct of writers. A recent article in

Scientific America A Learning Secret: Don’t Take Notes with a Laptop

examined ongoing research comparing students who took notes by hand during

lectures and those who typed notes direct into a keypad. The studies found that

the students who had computers managed to copy down more words than those who

wrote by hand. However it was the students who wrote by hand who retained more

memory of the lecture afterwards.

The very fact that writing is

a slow craft meant that students who wrote were obliged to focus more on the essence of

what was being said. As they wrote they automatically filtered, summarised and

weighed the value of the words spoken so that they could jot down what was

really important. All of this takes more effort than copying words onto a

screen, but it was this very effort that produce a greater engagement with the

lecture. The written notes also seemed to provide more ‘effective memory cues

by recreating the context (e.g., thought processes, emotions, conclusions) as

well as content (e.g., individual facts) from the original learning session.’

There can be no doubt about

the benefits of Information Age, yet it would seem that the very ease of the

interconnected world carries within it the danger of missing deeper slower

engagements. So the next time you’re in a lecture remember to GO SLOW and write

your notes by hand, that way you will make your brain retain the information and

not your computer.

Related articles:

* * *

For more on how to look good,

feel good and be in charge of your life as a student at NUI Galway check out Student's

Services Health Promotion Students at NUI Galway can also sign

up for the free online health and wellness magazine Student Health 101

No comments:

Post a Comment